What Trail Runners Can Learn from Cycling’s Doping Era

Pro cycling showed us exactly how this story ends. Will we listen?

Ultrarunning loves to pretend it’s a wholesome, purist sport full of dirtbag runners just "out there for the experience." Meanwhile, elite road and track athletes get popped left and right for doping (WADA found 132 anti-doping rule violations in athletics in 2020 according to their annual report), and yet somehow we think ultrarunners—who push their bodies hard for hours on end—are all just out here thriving on high carbs, exogenous ketones, and vibes? No unified governing body, no out-of-competition drug testing, and yet we’re supposed to believe this sport is completely clean, and will stay that way? Okay.

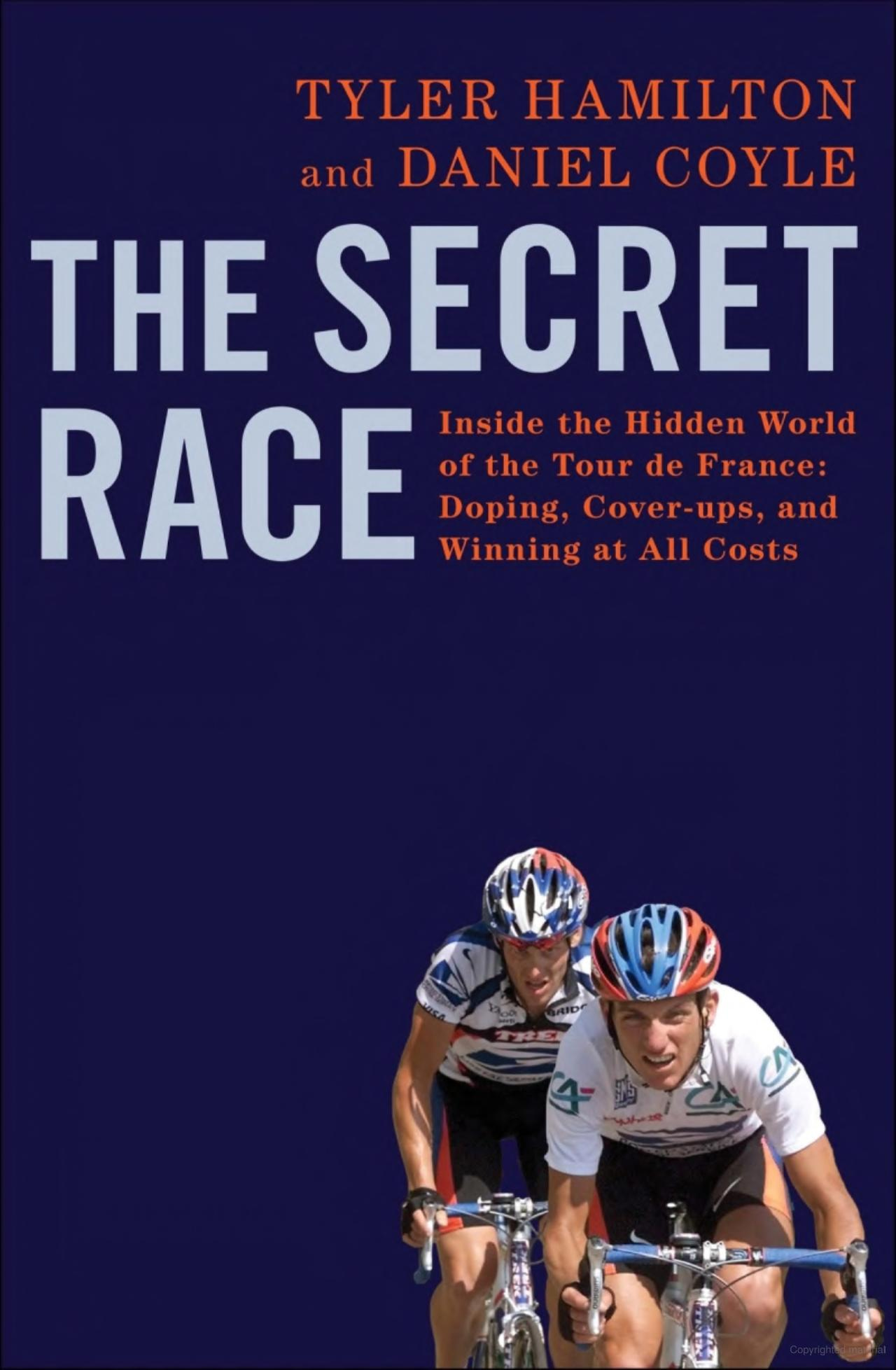

I know, I know, we’ve all heard enough over the past few weeks. Since Stian Angermund went on Freetrail to tell his side of the story, there have been so many reaction podcasts and conversations about anti-doping that I’ve been feeling overwhelmed. But I’ve thought about this enough now that I want to put my take out there. My buddy Finn recommended reading The Secret Race by ex-doper and ex-pro cyclist Tyler Hamilton. A couple days later, I’d finished it—and my biggest takeaway? If I were a pro cyclist in the early 2000s, I would have doped.

Cycling didn’t start as a dirty sport. It became that way because the incentive to dope outweighed the risk of getting caught. Using performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) was so commonplace in cycling in the late 1990s and early 2000s that it was impossible to compete at the highest level in the sport without them. The moment clean riders realized they had no shot without PEDs, they had two choices: get on board, or get left behind. If you’re a driven, competitive person—even if you’re also a nice, likable, honest person—you can justify doping when everyone around you is doing it. Ultrarunning might not be there yet, but as prize money, sponsorships, and prestige grow, we’re walking the exact same path. And as we can learn from cycling, it’s a tough process to clean up a dirty sport and change public opinion.

“It’s not really cheating because it’s not an unfair advantage, everyone smart enough to dope in an undetectable way is also getting that advantage.”

“It’s regrettably just an unavoidable part of the game.”

These were common sentiments in that era of cycling. Good people doped, and bad people doped. Nice guys and jerks. Also there were good people and bad people who didn’t dope and made up the back of the peloton. Or who just quit the sport altogether. There doesn’t seem to be a direct correlation between people who doped and how kind or respected they were, because it was just part of the game. And there was another important part of the game: keep your mouth shut. When questioned, they nearly all publicly lied about it until there was proof that they were dirty and then they’d get suspended or banned, and appeal the decision or retire.

I’m definitely not trying to say that Stian doped and is a cheater. I also can’t say that I know that he didn’t cheat. Either way, he’s unfortunately the face of doping controversy right now as one of the first big names in the sport to test positive after winning UTMB’s OCC in 2023. The interview with him made me want to believe he’s innocent, he seems like a great guy who has truly suffered as a result of this, and his timeline for being notified of the results of this test does seem unfair to him. Tyler Hamilton’s story about his cycling experiences made me realize that what Stian said and did is what most athletes, clean or dirty, would say and do if they wanted to continue competing. Ultimately it doesn’t really matter what we think about his guilt or innocence in this particular case, what matters is that we keep the culture of ultrarunning one where the elite athletes’ perception is that you can trust the system, be clean, and still compete at the highest level—because as soon as that isn’t the case, the doping floodgates open.

The impression that I currently have of ultrarunning is that winning performances, while often very impressive, are within the realm of humanly possible without being chemically enhanced. Maybe I’m naive, but in today’s world I don’t think you have to cheat to win in ultras. Though there are likely a few exceptions, I’d bet that most of the figures we look up to in the sport are clean. As the sport continues to grow and more money comes in, athletes have the potential for larger contracts and higher bonuses for race results. Eventually, some invisible threshold is crossed where it will be financially viable to pay for the drugs, doctors, equipment, etc. needed to dope “safely.”

Testing the top few finishers of the world’s biggest races is a start, but fairly meaningless—especially when the fairness of that testing process is called into question like in Stian’s situation. Without random, out-of-competition testing, there’s nothing (besides personal integrity and financial limitations) to prevent athletes from using PEDs in training to get unnaturally fit, then going clean far enough ahead of a race for everything to be out of their system in time for a urine test. Biological passports could also be implemented to track baseline levels in blood and can help determine if athletes are receiving blood transfusions or cheating in more sophisticated ways. These testing practices are common in more established sports like cycling and athletics. What’s so different about trail running? Kilian Jornet sums it up well with his statement in this TrailRunner Mag article—

“The problem with trail running is there isn’t an entity managing everything. So then it’s very hard to have out-of-competition controls.”

We lack a central organizing body and funding for expensive anti-doping programs. If we want ultrarunning to remain a sport where clean athletes can compete, we need to demand more than just occasional post-race testing. A real anti-doping system—random out-of-competition testing, biological passports, and a governing body with actual funding—isn’t a luxury, it’s a necessity. I’m certainly not the first person to say any of these things, but continuing the conversation is important if we want to see change. Check out this interview between Corrine Malcolm and Jason Koop on potential solutions to this problem. Groups like the Pro Trail Runners Association (PTRA) are pushing for improved testing and we’re seeing some slow progress, but if the sport keeps growing without real oversight, we’ll end up exactly where cycling was in the early 2000s. The only question is: do we want to fix it now, or wait until it’s too late?

Koop has been the only one talking about this and he’s repeatedly done thoughtful podcasts on it. Major ultra organizers (WS, UTMB, all golden ticket races) need to get on board with testing and now. It’s not cost effective to it for small races but the competitive ones where money is involved - testing should be mandatory as they do in every other sport.

Great post.

If there was anything I learned from reading that book it’s that testing on race day was a waste of time. If you are using PED’s then you know the glow time of these drugs. I think if someone gets caught in a race it’s probably contamination because you’d have to be stupid.